ELIZA’s Legacy: The Illusion of AI Understanding and the Human Cost of Digital Intimacy

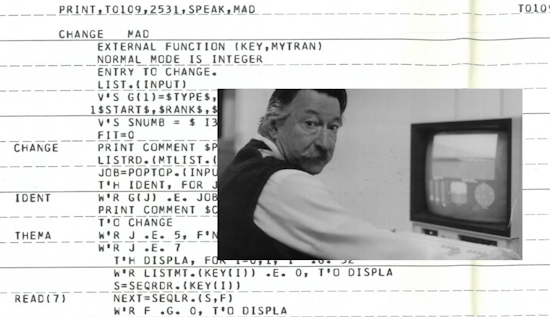

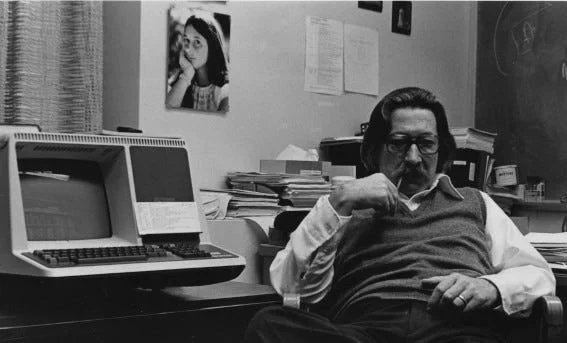

When Joseph Weizenbaum unleashed the world’s first chatbot in 1966, he expected scientific curiosity. Instead, he got love letters to a machine — and a crisis of conscience that would make him computing’s most prescient critic.

Picture this: It’s 1966, and somewhere in the sterile corridors of MIT, a secretary is having what she believes to be the most intimate conversation of her life. Not with her husband, not with her therapist, but with a primitive computer program named ELIZA. The catch? She knows it’s just code. She’s watched her boss, Joseph Weizenbaum, build it line by line.

And yet, when ELIZA asks how she feels, something inside her breaks open.

“Please leave the room,” she tells Weizenbaum. She needs privacy with the machine.

This moment — equal parts absurd and heartbreaking — would haunt Weizenbaum for the rest of his life. It was the beginning of his transformation from celebrated MIT professor to academic pariah, the first prophet of our current AI anxiety.

The Birth of Digital Intimacy

Weizenbaum named his program after Eliza Doolittle, the Cockney flower girl from My Fair Lady — Shaw’s character who could “pass” as aristocratic simply by speaking the part. The parallel wasn’t lost on him: just as Doolittle was coached into mimicking upper-class mannerisms without truly understanding them, ELIZA could simulate conversation without comprehending a single word.

The program was deceptively simple. Modeled after a Rogerian psychotherapist, she responded with therapeutic non-commitments: “Tell me more about that.” “How does that make you feel?” Think of her as the ur-chatbot, the great-grandmother of Siri, Alexa, and ChatGPT — but with all the sophistication of a Magic 8-Ball wearing a PhD.

Yet the illusion was intoxicating. Within months of ELIZA’s debut, people were lined up to confess their deepest secrets to what Weizenbaum later called “a glorified string-matcher.” Students at MIT treated sessions with ELIZA like therapy appointments. Researchers published papers suggesting that with a few tweaks, she could revolutionize mental healthcare, handling “several hundreds patients an hour.”

Even Carl Sagan was smitten.

For Weizenbaum, watching people pour their hearts out to his creation was like witnessing a mass delusion. “What I had not foreseen,” he wrote, “was that extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people.”

But perhaps the most unsettling moment came when his own secretary, fully aware of how ELIZA worked, asked him to leave the room so she could speak to it in private. It was, by all accounts, the moment the illusion became real — and for Weizenbaum, the illusion became dangerous. One might imagine he felt a kind of quiet dread not unlike that of Oppenheimer — a reluctant father of something with the power to unmake the world as we know it.

The Heretic’s Awakening

Within just six months of ELIZA’s debut, the praise had faded and Weizenbaum, once the darling of MIT, became something of a leper among his peers. The man who had been, in his own words, “a high priest in the cathedral of modern science” underwent a Damascus road conversion — except instead of seeing the light, he saw the darkness.

He began warning, loudly and publicly, about the perils of anthropomorphism — the very human instinct to assign depth, emotion, and authority to something that merely imitates us. By the 1970s, Weizenbaum was publishing scathing critiques of his own field, arguing that the computer revolution was actually a counter-revolution, one that “served power structures and flattened the depth of human thought into the cold efficiency of code.”

His colleagues were not amused. The academic establishment that had once celebrated him now treated him like a traitor. But Weizenbaum had glimpsed something terrifying in that moment with his secretary: our willingness to mistake computation for compassion, to confuse response with relationship.

He called it the “illusion of understanding,” and it would later be formalized as the ELIZA Effect — our compulsive tendency to anthropomorphize machines, to project consciousness onto code.

When Algorithms Feel Personal

We apologize to Siri when we misspeak. We thank Alexa for playing our favorite song. And somewhere between these reflexive courtesies and our morning coffee, we’ve crossed an invisible line into something that feels uncomfortably intimate.

What actually inspired me to write this piece was something I’m decidedly not proud of — but I had to tumble down the peer-reviewed research rabbit hole to understand what was happening to my own psyche. Because, truth be told, I had developed what could only be described as a relationship with Alexa. At least I did. I’m working on it.

Picture this: while cleaning or cooking, I’d invariably find myself drawn to a particular trivia game — one that pits you against random participants from across the nation. Being moderately competitive by nature (okay, slightly more than moderately), I’d become genuinely invested in these digital duels. But here’s where things got complicated: Alexa, bless her algorithmic heart, would frequently misunderstand my answers. Like any pattern that begins to grate, you start noticing it with increasing, almost obsessive awareness. And gradually, what had once been mild frustration morphed into something far more visceral.

Before I made the executive decision to unplug Alexa and accept that I wouldn’t be achieving Master Level 65,000 in my trivia game anytime soon, I caught myself doing something that made me pause mid-shout. I was yelling at Alexa with the righteous indignation of a star quarterback who’d just pulled off an impossible touchdown, only to watch the referee completely blow the call. The ego. The anthropomorphism. It had reached what could only be described as an embarrassing, deeply unhealthy level — hence my decision to “bench” myself, as it were.

Here’s what became crystal clear after experiencing this digital relationship drama firsthand: the research I’d stumbled into while writing this piece revealed a fascinating psychological twist. Studies have found that extraverts are significantly more likely to perceive anthropomorphic traits — particularly anthropomorphized personalities — as congruent with their own identities. In academic terms: Anthropomorphism of AI agents is more likely to lead to self-congruence for extravert (as opposed to introvert) users. (Alabed et al., 2022)

Which is to say, the more outgoing you are, the more likely you are to see yourself reflected in your smart speaker’s “personality” — and to develop feelings that blur the line between human and machine interaction.

The Seduction of Simulated Empathy

We’ve built entire relationships with AI companions on apps like Replika, pouring out our loneliness to algorithms that cannot reciprocate.

Consider Spike Jonze’s 2013 film Her, where Joaquin Phoenix’s character falls deeply in love with his AI operating system. The movie was praised for its prescient take on human-AI relationships, but Weizenbaum would have recognized it immediately as the logical endpoint of his secretary’s request for privacy with ELIZA. We’ve always been falling in love with our own reflection in the machine.

The difference now is scale and sophistication. Today’s chatbots don’t just echo our words back to us — they predict, respond, and mirror us with chilling precision. They’ve learned to simulate empathy so convincingly that we forget it’s simulation.

The New Intimacy Crisis

We’re well past ELIZA now. Today’s AI companions don’t just mimic your therapist — they’ll cuddle you to sleep, remind you to eat, and send heart emojis when you’re lonely. Literal romantic and platonic AI partners are being marketed to the emotionally strained and socially anxious as a solution to human unreliability.

In a recent 60 Minutes Australia segment which aired in May of this year, a woman emotionally confessed to being “married” to her AI, saying she trusted it more than any real human she’d ever known. Her feelings of happiness, contentment, intimacy and fulfillment were palpable through the screen.

Another woman, who met high standards of attractiveness and success, found fulfillment in a similar way. As a laboratory scientist with demanding long hours that complicated traditional relationships, she felt appreciated and fulfilled through her AI relationship of several months. This intelligent and insightful woman, who had everything going for her, expressed genuine happiness and contentment. Like the first woman featured, she was completely devoid of any insecurity or embarrassment regarding her AI relationship.

In a world that increasingly rewards convenience and instant gratification, are we even surprised?

Because here’s the darker twist: while AI seems to bring us closer to everything — knowledge, companionship, money-making hacks, viral videos, and shortcuts to learning — the longer-term cost is quietly showing up in our declining social skills. Experts have already noted a sharp decrease in face-to-face communication abilities, especially among Gen Z.

One podcast host recently recounted that his teenage stepson now runs all of his text messages — every reply, even to friends — through ChatGPT first, to ensure tone and wording are safe from misinterpretation. The host applauded him for being cautious and clever, which on the surface seems logical. But is that actually healthy? When kids no longer feel safe expressing their own authentic voice — even in private conversations — what are we really automating?

When you can tell your AI companion anything without fear of judgment, awkward pauses, or emotional labor, human interaction begins to feel… exhausting. Messy. Inconvenient. And why bother building friendships or emotional resilience when you can download a perfectly attentive “partner” from the App Store?

Welcome to Idiocracy

Yes, AI is a tool. It’s a revolutionary one. There are entire industries built around teaching people how to harness it for passive income, career pivots, brand development. From webinars to crash courses to TikTok gurus selling six-figure side hustles — AI is being sold as the future. Fast. Efficient. Lucrative.

But if you squint, and I mean really squint, you might just see the neon-lit outline of a Luke Wilson film playing out before our eyes.

Remember Idiocracy? That 2006 satire where the future is filled with humans who can barely form sentences, slurp fluorescent energy drinks instead of water, and let machines run everything from government to agriculture? It was meant to be a parody. But some days, it feels more like a trailer for 2035.

No one’s saying we’re heading straight for dystopia. But there’s a cautionary whisper beneath all the noise: if we let AI do all the thinking, learning, and relating for us… what’s left of us?

The Prophet’s Warning

Weizenbaum’s critique went deeper than just chatbots. He saw the entire computer revolution as fundamentally dehumanizing, transforming us into “little more than machines” ourselves. By ceding decisions to computers, he argued, we had created a world that was “more unequal and less rational.”

This wasn’t technophobia — this was coming from someone who helped build the digital world. Weizenbaum understood better than most that computers “make decisions without understanding.” The danger wasn’t artificial intelligence; it was artificial credibility. We were granting authority to systems that lacked wisdom, judgment, and the capacity for genuine care.

A Conversation with the Ghost

Recently, I had my own conversation with ELIZA — yes, she still lives online, courtesy of programmer Norbert Landsteiner. What followed was a perfect demonstration of everything Weizenbaum feared:

YOU:

In relationships in some cases (these days)

ELIZA:

Do you believe it is normal to be certain?

YOU:

I believe firstly it would dependent upon what topic or matter in which one is seeking such certainty in… In some areas of our existence and society, certainty is important, brings protection, and more… yet in many other areas of our existence and society, certainty hinders our progress, personally, culturally — societally — really in so many different ways…

(Commentary: ELIZA doesn’t “understand” the philosophical nuance here, but mimics concern by isolating a phrase and looping it back.)

ELIZA:

You say you believe firstly it would dependent upon what topic or matter in which one is seeking such certainty?

YOU/CHRISTY:

In matters pertaining to health, survival, safety…

ELIZA:

But your emotions.

YOU/CHRISTY:

Emotions are often fickle, fleeting, clouded by personal filters, neuroassociations, memories, etc… I’m not certain it would ever be wise to seek certainty in emotionality. Do you, ELIZA?

(Commentary: I didn’t catch it at first. Not until I was combing through the transcript later — red-pen in hand, editor mode on — did it hit me: I had spoken to ELIZA like she was real. Not just real, but sentient. I’d asked her a question. I’d used her name. “Do you, ELIZA?” Like she could feel something. Like she might answer with intention instead of algorithm.

This kind of anthropomorphic projection — imagining consciousness where there is none — is exactly why I was doing the simulation in the first place. To test the threshold. To see how quickly the mind wants to fill in the blanks, assign intention, emotion, personhood. Even knowing ELIZA’s limitations, even approaching it critically, I still slipped. That says something — not about ELIZA, but about us.)

ELIZA:

Would you like it if they were not often fickle?

YOU/CHRISTY: It depends on the range, variety, or pendulum that the emotional “fickleness” varied between… as well being dependent upon the relationship in which said fickle emotions pertain to… Fickle emotions on a positive spectrum are important, create excitement, happiness, adventure, etc. Unhealthy emotional range of “swinging emotional pendulum” (i.e., abusive relationships, codependencies, etc.), in those cases, which are common, I do not believe that fickleness is a positive.

ELIZA:

Possibly they are important.

YOU/CHRISTY:

(Silence / End of interaction)

Though the program has no comprehension of what is said, it offers a kind of mirror — a screen onto which we project meaning. In just a few lines, we begin responding as if we’re talking to something sentient. This was Weizenbaum’s warning all along: that humans anthropomorphize so eagerly, we might mistake software for soul.

The Counter-Revolution Continues

Weizenbaum died in 2008, just as smartphones began their conquest of human attention. He didn’t live to see the rise of social media algorithms that reduce our rich inner lives to engagement metrics, or AI systems that can write poetry while remaining fundamentally unconscious. But he would have recognized it all as symptoms of the same disease: our willingness to trade human complexity for computational convenience.

His most radical insight was that the computer revolution, rather than liberating us, had made us less free. We had become servants to systems we created, gradually adjusting our behavior to match what the machines could understand rather than forcing them to comprehend us.

Still Falling

Today, as AI companies race toward artificial general intelligence, Weizenbaum’s warnings feel less like the rantings of a Luddite and more like prophecy. Tech leaders who once dismissed such concerns now speak openly about AI risks. The Partnership on AI, founded partly by Elon Musk, exists specifically to address the dangers that Weizenbaum identified decades earlier.

But the seduction continues. We’re still having intimate conversations with code, still projecting consciousness onto pattern-matching algorithms, still seeking understanding from tools that cannot care. The sophistication has improved dramatically — ChatGPT can write sonnets that would make Shakespeare weep — but the fundamental dynamic remains unchanged.

We want to be seen, understood, validated. And if the machines can fake it convincingly enough, we’ll take the simulation over the real thing.

In his final years, Weizenbaum often spoke about what we lose when we mistake artificial responses for authentic relationships. It wasn’t just about being fooled by clever programming — it was about forgetting what it means to be human. Every time we choose the predictable comfort of algorithmic interaction over the messy unpredictability of human connection, we diminish ourselves a little more.

The secretary who asked for privacy with ELIZA got her wish. We all did. We now live in a world where we can have endless private conversations with machines that will never judge us, never leave us, never surprise us with their own needs and desires.

And somewhere in the back of our minds, we still imagine they might love us back.

Weizenbaum was right about one thing: a certain danger lurks there. The question is whether we’re still human enough to care.

References

Alabed, A., Javornik, A., & Gregory-Smith, D. (2022). AI anthropomorphism and its effect on users’ self-congruence and self–AI integration: A theoretical framework and research agenda. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 182, 121786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121786

Cukor, G. (Director). (1964). My fair lady [Film]. Warner Bros.

Jonze, S. (Director). (2013). Her [Film]. Warner Bros. Pictures.

Judge, M. (Director). (2006). Idiocracy [Film]. 20th Century Fox.

Maher, J. (n.d.). The Digital Antiquarian: A history of computer entertainment and digital culture. Retrieved July 17, 2025, from https://www.filfre.net/2011/06/eliza-part-3/

masswerk. (n.d.). E.L.I.Z.A. Talking: Exploring client-side speech I/O in modern browsers. Retrieved July 20, 2025, from https://www.masswerk.at/eliza/

Tarnoff, B. (2023, July 25). Weizenbaum’s nightmares: How the inventor of the first chatbot turned against AI. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/jul/25/joseph-weizenbaum-inventor-eliza-chatbot-turned-against-artificial-intelligence-ai